The Praise of Folly: A Brief Introduction

more chilling than Machiavelli; more detached than Montaigne

“In the Praise of Folly Erasmus gave something that no one else could have given the world,” wrote the Dutch historian, Johan Huizinga.1

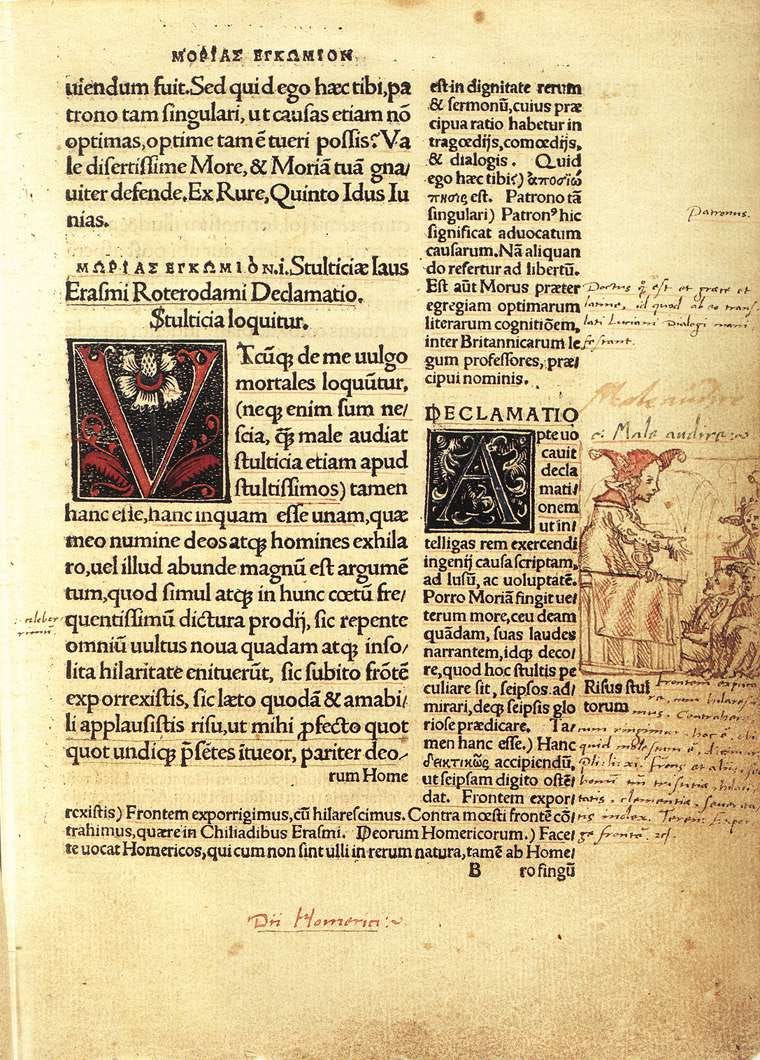

Erasmus conceived of his Moriae Encomium while passing the time on a long horse ride over the Alps from Italy to Dover where he would sail to England to convene with fellow humanist, Thomas More, “the most witty and wise of all his friends.”2

In his preface to the Praise of Folly, which is dedicated to More, Erasmus explains that rather than waste his time with “foolish and illiterate fables,” he occupied his mind thinking of his friends and their common studies (humanities).3 The first to come to his mind was More. Erasmus pondered the fact that More’s surname was so close, etymologically, to the Greek word for fool, Moriae, when his character was so far from the thing.

He delighted in More’s affability, sweetness of temper, love for witty, mirthful literature and excellence of judgment. Comparing him to Democritus, the Ancient Greek atomist who was known as the “laughing philosopher” for his perpetual jest at human folly, Erasmus conceived of More as one who carried himself “to all men a man of all hours.” It was on that ride in 1509 that Erasmus “resolved to make some sport with the praise of folly” and claimed to have penned it down in a matter of a few days after he arrived in England.

A Digressio: Erasmus Being Dead, Yet Speaketh

Of interest in regards to Erasmus’s legacy, it is probable—at the very least, it’s conceivable—that his expression in the preface describing More as being “to all men a man of all hours” was the inspiration for a later more memorable expression carrying the same meaning. The English humanist schoolmaster, Robert Whittington, described Thomas More as “a man for all seasons” in his 1519 schoolbook, Vulgaria. In his textbook, Whittington closely echoes Erasmus’s particular description of More in the dedicatory preface to the Praise of Folly. Whittington wrote,

“More is a man of an angel’s wit and singular learning… a man of marvelous mirth and pastimes, and yet the same man is a man of great gravity. What cannot he do? As a man of all occasions, he is a man for all seasons” (emphasis mine).

Four hundred years later, Robert Bolt would capture Whittington’s more memorable expression as the title of his play about the life of Thomas More. In July of 1960, Bolt’s play A Man for All Seasons was performed first in London at the Globe Theatre, then on Broadway, and eventually it became “a multi-Academy Award-winning 1966 feature film and a 1988 television movie.”

An Apology

Erasmus defends his use of “biting” literature, what we would today call satire, arguing his was not the first of its kind. He offers this apology, not because More would object—More would publish his own satirical work, Utopia, a few years later in 1516—but because of those “wranglers” and “cavilers” who undoubtedly would be offended at his immodest use of language as unbecoming of a divine or a Christian. After providing a long list of great authors who also used satire to teach a moral lesson, Erasmus asserts his apologia for the work:

For what injustice is it that when we allow every course of life its recreation, that study only should have none? Especially when such toys are not without their serious matter, and foolery is so handled that the reader that is not altogether thick-skulled may reap more benefit from it than from some men’s crawfish and specious arguments…nothing is more trifling than to treat of serious matters trifling, so nothing carries a better grace than so to discourse of trifles as a man may seem to have intend them least…I have praise folly, but not altogether foolishly. And now to say somewhat to that other cavil, of biting (satire). This liberty was ever permitted to all men’s wits, to make their smart, witty reflections on the common errors of mankind, and that too without offense, as long as this liberty does not run into licentiousness.

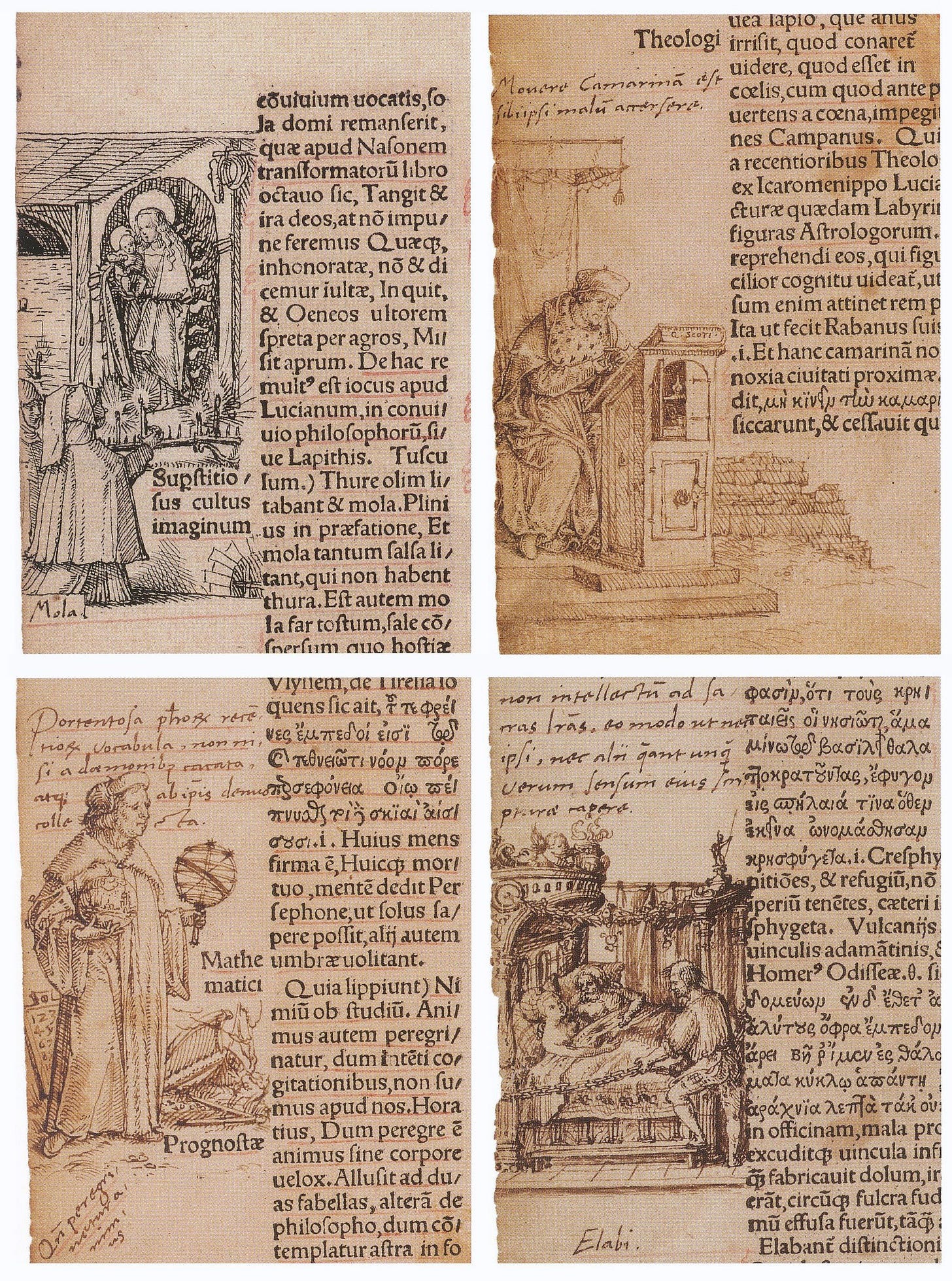

The Form and Imagery

Having already been appraised that the Praise of Folly is a satirical work confronting the vices and follies of the human race, what of its form and imagery?

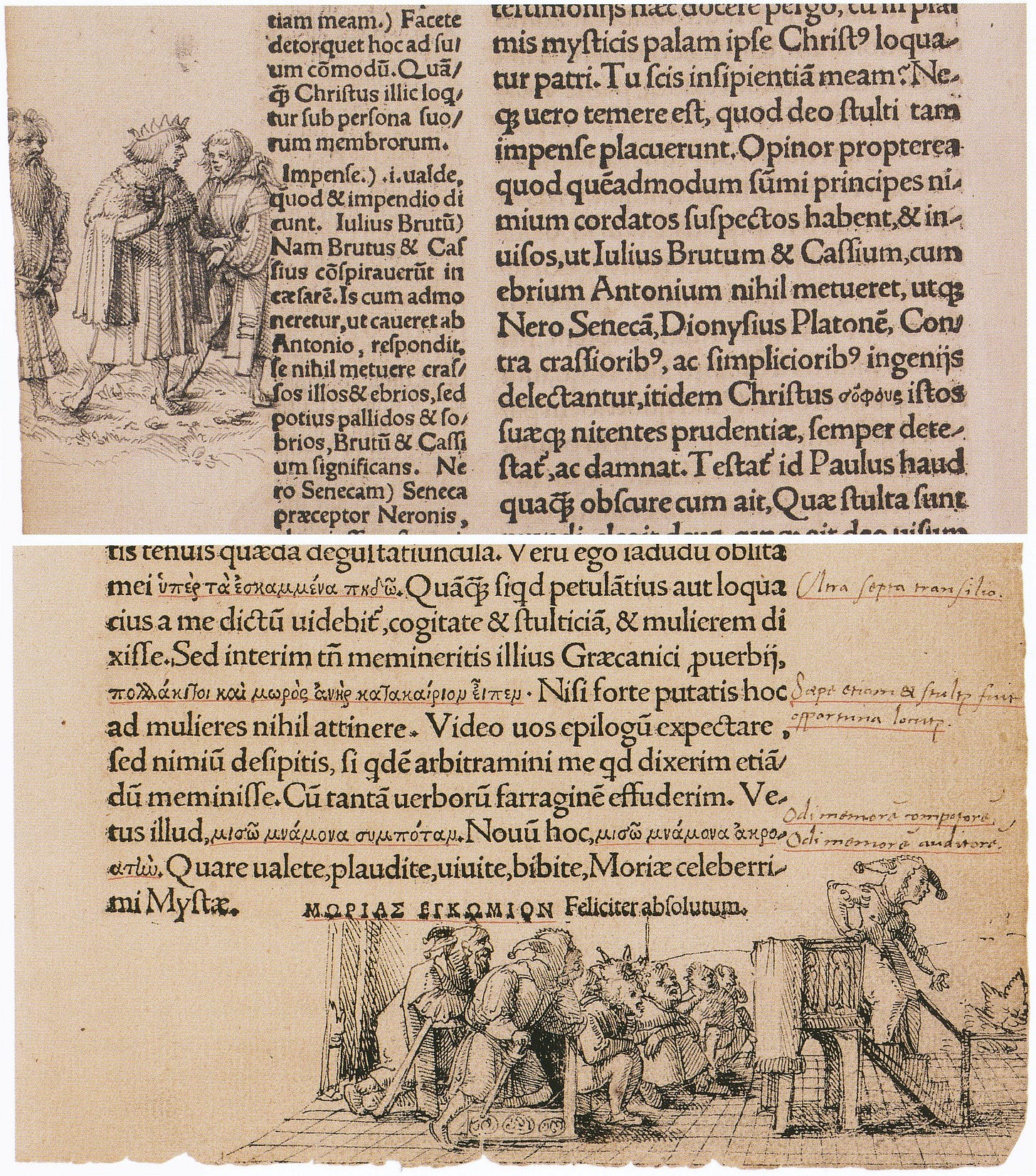

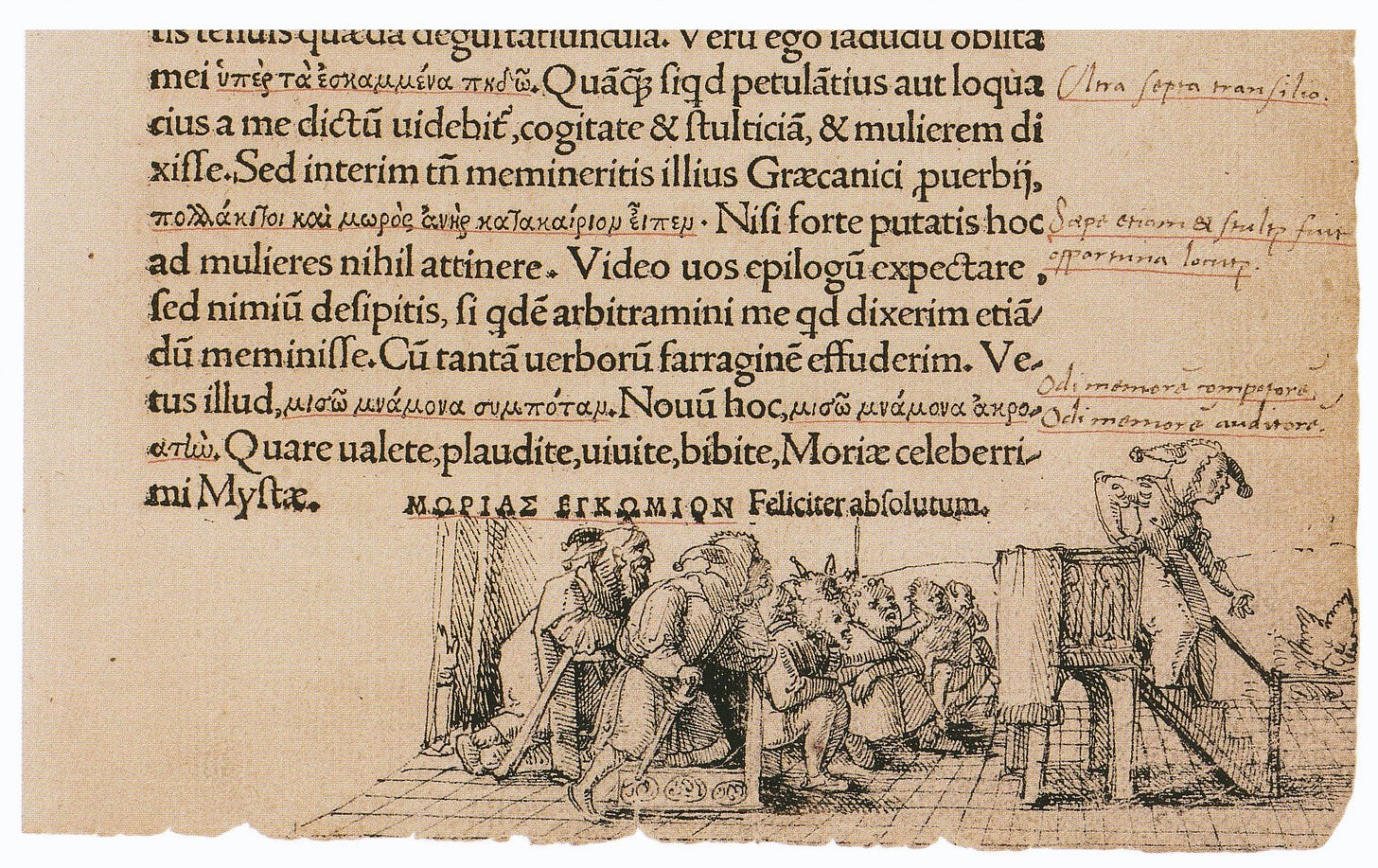

For its form, Erasmus draws heavily from the style of Libanius, the Greek sophist, in that he has Dame Folly deliver a declamation to her eager audience. In spirit, Erasmus draws from the Roman satirist, Lucian, whose works he had previously translated. As for the artistic imagery of the work, Huizinga rightly compares Erasmus to Rabelais, whose grotesque Gargantua and Pantagruel would later be published serially from 1532–64.

They both used laughter as their moralizing medicine. But unlike Erasmus, Rabelais’s humor is exuberant and bawdy; and, he mocks the foibles and follies of society using an exaggerated, carnivalesque style. Yet, like Rabelais, Erasmus also uses humor to reveal human folly and call for a renewal of genuine Christian piety, but instead of enlisting ribald parodies to invoke laughter, Erasmus leans on a more urbane irony for his humor.

To get at the meaning of his Encomium, the reader must be careful to note that from the time she mounts the pulpit, Lady Folly’s entire declamation is a circulus vitiosus (a vicious circle) in which she postulates on the necessity of all human activity being driven by self-love. Acting as the counterpart to Pallas Athena, she is the voice of “worldly wisdom, resignation, and lenient judgement.” In her speech, “wisdom is to folly as reason is to passion.” Without folly and passion, man cannot truly live, she argues. His life is a comedy in which he is expected to conform to the existing conditions and play his part without question. If he attempts to be too serious, too reasonable, or to pull off his mask and quit the game as it were, he will be ejected from human society. Without folly, life is intolerable and impossible.

The Gist of the Encomium

After a long introduction in which Folly unpacks her pedigree as a goddess, she lays out her arguments for her place as alpha among all the gods. She alone is the one who bestows all things on all men. “In fine,” says Lady Folly,

I am so necessary to the making of all society and manner of life both delightful and lasting, that neither would the people long endure their governors, nor the servant his master, nor the master his footman, nor the scholar his tutor, nor one friend another, nor the wife her husband, nor the usurer the borrower, nor a soldier his commander, nor one companion another, unless all of them had their interchangeable failings, one while flattering, other while prudently conniving, and generally sweetening one another with some small relish of folly.

Erasmus’s satirical exercise in social criticism “is bolder and more chilling than Machiavelli, more detached than Montaigne,” claims Huizinga. It’s a masterpiece of artistic perfection whose whole “presents a perfect instance of that harmony which is the essence of Renaissance expression.” Of all Erasmus’s works—and he wrote many more important and influential in his day—the Praise of Folly is considered by many to be his best work. And even if Erasmus would be disappointed with that legacy, it’s inarguable that of his collected works, “Moraie Encomium alone was to be immortal.”

For the month of October, the Tsundoku Reading Society read the Praise of Folly, together. You can download a free PDF of the work below. If you’re interested in joining us for the Tsundoku Reading Society today, just become a paid subscriber. I’ll email you a Zoom link shortly.

Today’s meeting is Monday, October 27th at 4:00 pm PT / 7:00 pm ET.

October Giveaway

When you become a paid subscriber, you’ll get access to the growing resource page, all the archived content, and free books when I publish them. Plus, once you join our merry band of bards, bishops, and bibliophiles, students, scholars, and philosophers, and poets, preachers, and pirates, you’ll also be entered into a drawing for a chance at October’s Giveaway—Erasmus of Rotterdam: The Spirit of a Scholar by William Barker. It’s a beautifully bound and illustrated biography of our famed Christian Humanist. I’ll draw a random name and announce the winner at the end of the month.

Johan Huizinga, Erasmus and the Age of Reformation: With a Selection of Letters from Erasmus (New York, NY: Harper Torchbooks, 1957), 78.

Huizinga, Erasmus and the Age of Reformation, 69.

John Wilson and Desiderius Erasmus, In Praise of Folly (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2003), 1.