Xenia and the Great Commandments

Separating the civilized from the barbarians

If Helen is the face that launched a thousand ships, then Homer is, undoubtedly, the pen that inspired a thousand poets. Though Homer first penned his epics, The Iliad and The Odyssey, approximately three millennia ago, the myths had been recited for at least four hundred years prior. As some of the oldest surviving epics, they are, literally, the foundational works of Western literature. To rework a Tolkien metaphor, Homer’s “Cauldron of Story” has been boiling for more than three thousand years, and we still use its stock to make our soup today, and expect our posterity will too, for several millennia to follow.

So the question naturally arises: what is it about the Homeric epics that have resonated so deeply with readers for the past thirty-two centuries? What is so significant about these poems that they have compelled so many generations to use the stock from the Homeric cauldron to make their own soup? Why do we still recite these poems, still reread them, and still re-purpose them with such alacrity?

Heroic Ethos

One answer might be the hero narratives that drive the epics’ plots. The heroic aspect touches that thymatic part of the human soul where the hero exists in all of us. Examples that testify to the venerability and versatility of the heroic narratives are legion in both life and literature.

For example, one contemporary Psychiatrist, Jonathan Shay, has accomplished ground-breaking work using The Iliad and The Odyssey to treat veterans with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Through his own personal traumatic experience, Dr. Shay began reading the classics and discovered many of his patients at the V.A. clinic were wrestling with issues similar to the Greek warriors of the Homeric Epics: “betrayal by those in power, guilt for surviving, deep alienation on their return from war.”

Realizing the heroes of Homeric epics were telling the same deeply human stories as the modern warriors he was treating, he was able to make significant advancements in treating patients with PTSD.

The poet, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, also found inspiration in the heroic narrative. His Poem, Ulysses (the Roman transliteration for Odysseus), is one of early Victorian literature’s finest bowls of Homeric-based soup. Consider the last stanza where the aged Odysseus beholds the ship and harbor while he contemplates his final adventure:

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

'T is not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

For one who has not read The Odyssey, Tennyson’s poem will lack the potency intrinsic in the Homeric Cauldron of Story, but for those who have, it is impossible to miss the hearty flavor of the heroic heart.

Tennyson indubitably draws from Teiresias’ prophecy concerning Odysseus when he looked into Hades: “Death will come to you from the sea, in some altogether unwarlike way, and it will end you in the ebbing time of a sleek old age.”

The heroic heart is a heart of one equal temper, one which is common to all those who desire knowledge and adventure, those who desire to “drink life to the lees.” As long as there are men who, though made weak by time and fate, have the strong will to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield, there will be poets who make their soup from the Homeric Cauldron of Story, and people enough for a thousand generations to eat it.

Of course, the hero narrative touches only one part of the human soul, the thymatic. Yet, the Greeks recognized three parts to the human soul: noetic, thymatic, and epithymatic.

Being some of the first to record their exploration of the human experience, the Greeks recognized good poetry, poetry that accomplished the enlightening and delighting of its hearers, had to touch all three parts of the person: the head, the heart, and the passions—and in a particular manner. To quote C. S. Lewis, “The head must rule the belly through the chest.”

Additionally, many readers will recognize the development of this particular philosophy of the soul in the art of rhetoric—persuasive communication that appeals to the logos, ethos, and pathos. This would suggest the heroic ethos can only account for a small part of the Homeric epics’ longevity and success.

In what follows, I would like to assert that if we dip our ladle a little deeper into Homer’s Cauldron of Story, we will discover some other, more nourishing bits worth our indulgence, the gravitas of ξενἰα, the ancient hospitality code.

It is my believe that the ancient hospitality code is of inestimable importance to the Homeric epics because it is of inestimable importance to the human experience. It is quite possibly the pervading theme contributing most to the underlying significance and longevity of the Homeric enterprise because it touches our humanity the deepest.

In the same way Jesus summarized the entire law and the prophets (Matthew 22:35-40) with just two commands that address the essence of all we are as humans—image bearers of God and brothers of all humanity—the Greek code of hospitality seems to summarize a similar essence of humanness, albeit framed within the contours of the Pagan Greek ethos.

As we plunge our ladle to the bottom of the Cauldron, let’s stir it a little so we get a better idea of its contents.

Background of the Homeric Epics

Epics are lengthy poems about the adventures and misfortunes of heroic characters. Composed in dactylic hexameter, the Homeric epics were traditionally sung by a rhapsode—a lyre-playing poet—during the feasts of the Greeks. Although there are several extant works that recount events related to the Trojan War, The Iliad and The Odyssey are the only two complete epics about this event to survive.

The Greeks of antiquity assigned the authorship of the epics to a poet they call Homer, believed to have been a blind bard living near the region of Ionia. Demodokos, the blind bard who is singing for Odysseus and the Phaiakians in book eight of The Odyssey, is possibly an allusion to, or self-portrait of, Homer:

[62] The herald came near, bringing with him the excellent singer

[63] whom the Muse had loved greatly, and gave him both good and evil.

[64] She reft him of his eyes, but she gave him the sweet singing

[65] art…

[479] For with all peoples upon the earth singers are entitled

[480] to be cherished and to their share of respect, since the Muse has taught them

[481] her own way, and since she loves all the company of singers.”

[482] So he spoke, and the herald took the portion and placed it

[483] in the hands of the hero Demodokos, who received it happily.

In the first stanza, the narrator tells us the bard was an excellent singer who had been blinded by the Muse, but given a sweet singing voice. In Greek mythology, the blind prophet or poet was a symbol that indicated they were bereft of physical sight because they had been given supernatural sight. Tiresias of Thebes is an example of this.

In the second stanza, Odysseus honors Demodokos with a rich piece of meat for his singing. The narrator then magnifies the importance of the bard’s place in society, calling him a hero, and saying he is entitled to be cherished and receive his share of the respect.

It is a strange episode, but its significance cannot be ignored, as it is not uncommon for artists to make a cameo appearance in their work. That said, there is some dispute among modern scholars whether or not the epics were written by the blind genius, singlehandedly. However, since the language and style of both epics are remarkably similar, and the authorship was undisputed among the Greeks of antiquity, most have not found sufficient reason to dismiss Homeric authorship of the epics altogether.

The date of their writing is, like their authorship, also disputed among modern scholars, but there seems to be substantial consensus that The Iliad was written down sometime around the eighth century B.C. shortly after the region emerged from the Greek Dark Age (1100-800 B.C.). The Odyssey is believed to have been written shortly after—at least within a single lifetime of The Iliad. Since the fall of Troy was likely to have occurred around the end of the Mycenaean Age (1600-1100 B.C.), and writing was non-existent during the Greek Dark Age, the epics are believed to have been transmitted orally for at about 400 years.

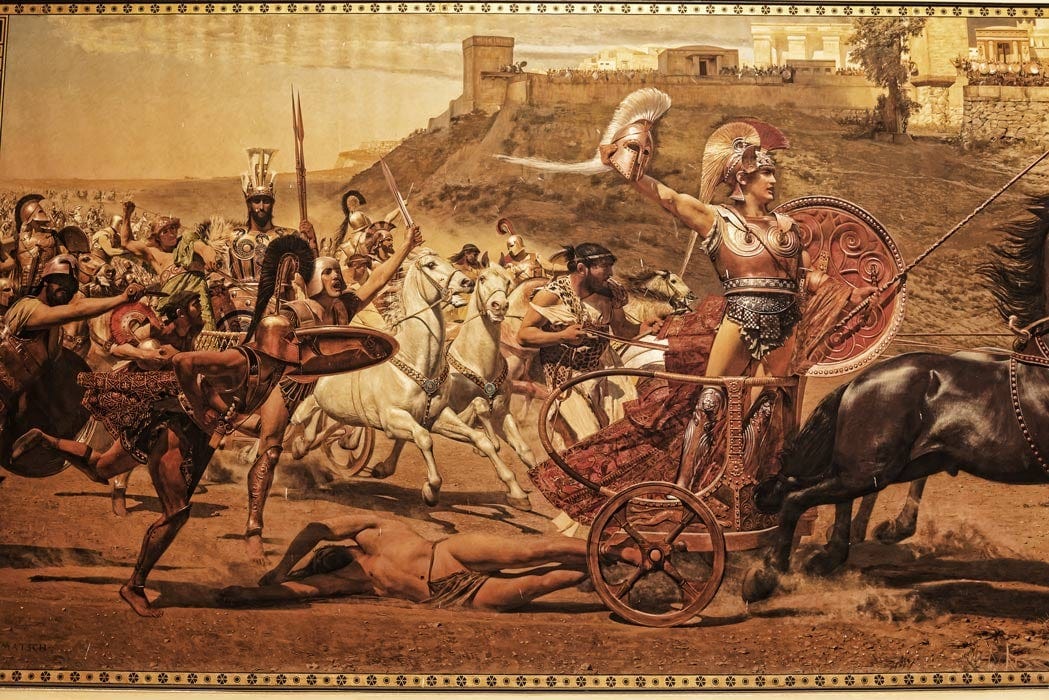

The Iliad is about an event that takes place in the tenth year of the Trojan War that results in devastation for the Achaians (An Homeric term for a large tribe of the Greeks), a conflict between Peleus’s son, Achilleus, and Atreus’s son, Agamemnon. It is best to say The Trojan War is the setting for the poem, but not its theme, as some have supposed. The major theme of The Iliad is found in the poem’s opening lines in book one:

[1] Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilleus

[2] and its devastation, which put pains thousandfold upon the Achaians,

[3] hurled in their multitudes to the house of Hades strong souls

[4] of heroes, but gave their bodies to be the delicate feasting

[5] of dogs, of all birds, and the will of Zeus was accomplished

[6] since that time when first there stood in division of conflict

[7] Atreus’ son the lord of men and brilliant Achilleus.

The narrator calls on the goddess, the Muse, to inspire him to tell the story of a great heroic tragedy. He begins his tale in medias res, a Latin expression that means in the middle of the thing. An Ionian or Greek audience would have known the story already, so beginning in the middle, where the action takes place, is the best place to begin an epic. It is interesting to note, this is schema is still used in modern storytelling.

The Odyssey is about the travels of Odysseus and the suffering he endures to finally get home to his wife, Penelope, and his son, Telemachus, after the Trojan War. It too picks up the story in medias res:

[1] Tell me, Muse, of the man of many ways, who was driven

[2] far journeys, after he had sacked Troy’s sacred citadel.

[3] Many were they whose cities he saw, whose minds he learned of,

[4] many the pains he suffered in his spirit on the wide sea,

[5] struggling for his own life and the homecoming of his companions.

[6] Even so he could not save his companions, hard though

[7] he strove to; they were destroyed by their own wild recklessness,

[8] fools, who devoured the oxen of Helios, the Sun God,

[9] and he took away the day of their homecoming. From some point

[10] here, goddess, daughter of Zeus, speak, and begin our story.

Just from the opening ten lines one can see the many themes and motifs that will inform the poem. The bard tells us Odysseus is one who has participated in the sacking of Troy and is called “the man of many ways.” Obviously, this links him to the character by the same name in The Iliad. Trying to find his way home to his family and estate, he is driven on far journeys, experiences much pain, sees many cities, learns from many minds, struggles to keep his life, suffers on the wide seas, and loses foolish and reckless companions, all the while trying not to further upset the gods.

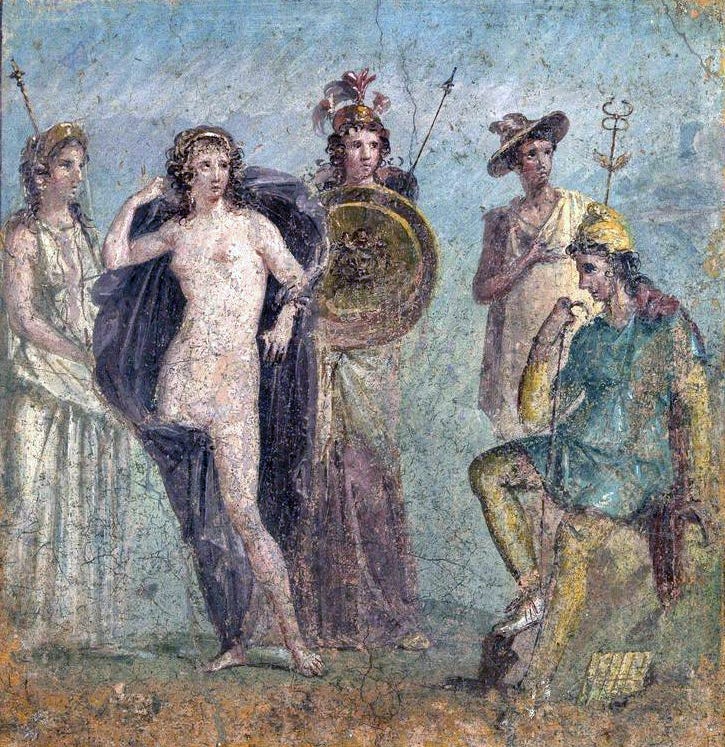

The backstory to The Iliad and The Odyssey is a myth called the judgment of Paris. It is not only relevant because it explains the reason for the Trojan War, but gets to the heart of the point I’m wanting to make here.

During the wedding feast of the mortal, Peleus, and the immortal sea nymph, Thetis (Achilleus’ parents), Eris, the goddess of discord, having not been invited to the wedding, tosses a golden apple to the dining party with the inscription, “to the fairest.” An argument ensues between Hera, the wife of Zeus, Athene, the goddess of wisdom and reason, and Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty who also happens to be the daughter of Zeus. Not wanting to get involved himself, Zeus asks Paris, a shepherd (who was also the abandoned son of Priam of Troy), to adjudicate between the striving goddesses. Each goddess offers Paris a prize for his favor: Hera offers power, Athene offers military strength, and Aphrodite offers him the most beautiful woman in the world.

Reminiscent of the stupid youth of Proverbs 7:21–23—With much seductive speech she persuades him; with her smooth talk she compels him. All at once he follows her, as an ox goes to the slaughter, or as a stag is caught fast till an arrow pierces its liver; as a bird rushes into a snare; he does not know that it will cost him his life—Paris chooses Aphrodite as the fairest. In turn, she gives him Helen, the divinely beautiful wife of Menelaos, king of Sparta.

With the help of Aphrodite, Paris abducts Helen from Menelaos, who, in turn, seeks his brother Agamemnon’s help. The Greek warrior-kings raise an expeditionary force of more than 1000 ships—1186 according to book two—and sail for Troy, also called Ilion, with the intent of sacking it. Thus, Helen is said to be the face that launched a thousand ships, and in Greek mythology, the reason for the Trojan War.

Interestingly, a number of modern scholars find it unlikely that the abduction of Helen could be the real reason for the Trojan War—if they believe there was really a Trojan War at all. These scholars suggest the epics are not historical narratives, but simply myths. Yet, a great number of others hold the epics to be mythologized historical tales, legends—mythologized tales, yes, but historical in some sense, nonetheless.

While many other explanations for the cause of the possible war are suggested and debated, a better understanding of the hospitality code in ancient Greece might suggest Helen’s abduction, or rather, Paris’s judgment for abducting Helen, is a plausible reason for a real long and bloody conflict between the Greeks and the Trojans.

Readers of the Homeric epics will quickly discover the mores of the ancient Grecian culture are much different than that of modernity, making it particularly important to read the epics with an awareness of one’s modern bias. The Greeks had a code of ethics rooted in polytheistic mythology, a limited and undeveloped view of the cosmos, and a completely different civic structure, comprised of a feudal-like warrior-king, agrarian and rapine economy, and chattel slavery. The bedrock of their civility was the hospitality code. This feature of society separated the civilized (by ancient standards) and the barbarians.

Xenia - The Ancient Code of Hospitality

To demonstrate the code, imagine a businessman on a trip to a metropolitan city, like New York or Chicago, showing up on the steps of a complete stranger’s house asking for a bed, a bath, or a meal. He would likely get himself run off; and in some cases, he might get himself injured or killed. As a matter of fact, in most cases society would caution such a person against entreating a complete stranger for lodging (or inviting a complete stranger into one’s home to lodge him). In the modern world, there are hotels and restaurants for such purposes. A complete stranger imploring a household for accommodations today would be suspect at best, and frightening or dangerous at worst. However, in the ancient world, few if any such enterprising accommodations existed, so travelers relied on the hospitality of strangers.

According to classicist, Dr. Elizabeth Vandiver, when the ancients traveled among their neighboring countryman for business and trade, a man would seek out a house that was near his own status and present himself as a foreigner-guest to the household. The local host had an obligation to receive the foreigner-guest.

This meant offering the foreigner-guest a meal, a bath, a place to sleep, and usually a gift. One important note is that the code required the host to serve the guest before asking his name. Likely this was an effort to maintain authenticity in showing hospitality before learning the identity of the guest.

The guest had a reciprocating obligation to respect the household and his host in a very particular way. At the very least, the foreigner-guest was never to plunder, or in any way disrespect, the possessions—especially the female persons—of the host’s household. A polite foreigner-guest would never overstay his welcome, and would frequently give a gift to the host in return. Because plundering the enemy for κλέος (glory), τιμή (honor), and γέρας (prizes) was a way of life in the ancient world, this hospitable exchange, called ξενἰα, was taken very seriously.

ξενἰα is often transliterated into English as xenia (ze-nia), and means roughly, but not specifically, hospitality, or guest-friend. A ξενἰος, the singular form (transliterated to English as xenos), can be a stranger, a guest, a host, or a foreigner. Although the semantical range for ξενἰος is rather vast, it is easy to see how the definitions all relate to one another. ξενἰα, the plural form, refers to the interaction or hospitable exchange between two ξενἰος.

As previously mentioned, ξενἰα was an extremely serious custom. Although there was no written rule about ξενἰα, per se, the understanding was tacit, and highly regarded among those who revered the gods, particularly Zeus. To violate ξενἰα was to dishonor Zeus, the chief among the Olympian gods, who often went by Ζεύς ξενἰος (Zeus Xenios), the god of hospitality. In book thirteen of the Iliad, and book nine of The Odyssey, Menelaos and Odysseus, respectively, refer to Zeus as “the guest’s god.” The fact that Zeus, the chief Olympian god, oversaw ξενἰα, directly, gives us further insight into the importance and gravity of this code.

One reason it was important to observe their particular level of hospitality so earnestly is the belief among the ancients that the gods often visited the mortals in the form of a stranger, as a ξενἰος. There is a remarkable example of this in the famous exchange between the Trojan warrior, Glaukos, and the Achaian warrior, Diomedes, in book six of The Iliad:

[119] Now Glaukos, sprung of Hippolochos, and the son of Tydeus

[120] came together in the space between the two armies, battle-bent.

[121] Now as these advancing came to one place and encountered,

[122] first to speak was Diomedes of the great war cry:

[123] “Who among mortal men are you, good friend? Since never

[124] before have I seen you in the fighting where men win glory,

[125] yet now you have come striding far out in front of all others

[126] in your great heart, who have dared stand up to my spear far-shadowing.

[127] Yet unhappy are those whose sons match warcraft against me.

[128] But if you are some one of the immortals come down from the bright sky,

[129] know that I will not fight against any god of the heaven

The exchange begins when Diomedes and Glaukos meet on the battlefield in close combat. Before engaging in melee, Diomedes, not recognizing his opponent, wants to be sure Glaukos is not one of the gods. He calls on Glaukos to reveal his identity, informs him that he will not fight against any god of the heaven, and then explains his reason by orating a beautiful chiastically-structured story of the destruction of Lycourgos, who assaulted Dionysos with an ox-goad. For his murderous actions, Lycourgos was stricken with blindness and did not live long because he was hated by the gods. Consider the words of Diomedes spoken to Glaukos:

[127] Yet unhappy are those whose sons match warcraft against me.

[128] But if you are some one of the immortals come down from the bright sky,

[129] know that I will not fight against any god of the heaven,

[130] since even the son of Dryas, Lykourgos the powerful, did not

[131] live long; he who tried to fight with gods of the bright sky,

[132] who once drove the fosterers of rapturous Dionysos

[133] headlong down the sacred Nyseian hill, and all of them

[134] shed and scattered their wands on the ground, stricken with an ox-goad

[135] by murderous Lykourgos, while Dionysos in terror

[136] dived into the salt surf, and Thetis took him to her bosom,

[137] frightened, with the strong shivers upon him at the man’s blustering.

[138] But the gods who live at their ease were angered with Lykourgos,

[139] and the son of Kronos struck him to blindness, nor did he live long

[140] afterwards, since he was hated by all the immortals.

[141] Therefore neither would I be willing to fight with the blessed

[142] gods; but if you are one of those mortals who eat what the soil yields,

[143] come nearer, so that sooner you may reach your appointed destruction.

While this kind of dialogue on the battlefield seems strange to our perception of warfare, it is important to keep in mind we are reading an epic sung by a bard to Greek warriors. The dramatic monologue here serves a bigger purpose than the poetic narration of a glorious battle scene.

By slowing down the narrative action and focusing closely on the warriors’ exchange, and in particular having Diomedes use a chiastic poem within the narrator’s broader poem, the poet is drawing his audience’s attention to something extremely important about the culture of these warriors. To say it another way, he is making a point to make a point.

Malcom Willcock helpfully suggests the following breakdown of Diomedes’ dialogue:

A) 127 A threat of death.

B) 128 But if you are one of the gods…

C) 129 I will not fight any of the gods…

D) 130-131 Lykourgos fought the gods and did not live long.

E) 132-139 The Account of Lycourgos’ actions.

D’)139-140 Lykourgos, hated by the gods, did not live long.

C’)141 So I will not be willing to fight the blessed gods…

B’)142 But if you are a man…

A’)143 A threat of death.

Homer, with a glorious display of poetic craftsmanship, interrupts the obstreperous, bloody battle and cunningly arrests his audience’s attention. Using the story of Lykourgos, told by the warrior, Diomedes, he reminds the Greeks there is a code of ethics that informs their society: in part, to fight against the gods is to bring upon oneself the full wrath and judgment of the gods. He reminds them they are religious men, which means, as we will see, they are hospitable men.

Again, the fact that a ξενἰος might be a god, speaks to the importance of serving the guest before asking his name. Seemingly, any preferential treatment based on one’s identity is unethical by their conventions. This ξενἰα code of the Greeks seems to be, in many ways, a rudimentary form of Jesus’s command to the Christians: “And he said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets.”” (Matthew 22:37–40, ESV).

In other words, it seems one of the most important codes within Greek culture was to honor the gods, and honor humanity by vulnerably showing non-preferential treatment to strangers.

Interestingly, echoes of this code were still informing the ancient near-east culture during the days of the Christ’s apostles, showing up in the letter to the Hebrews: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares” (Hebrews 13:2, ESV).

Reflecting on Abraham’s encounter with the Christophany in Genesis eighteen, the narrator warns believers they are not exempt from a divine visit. Though the Christian understanding of God is much different than that of the Homeric Greeks, there appears to be some striking similarities between the mythological Greek gods of Olympus and fallen angels of Genesis chapter six in the biblical narratives.

There is also a second aspect of ξενἰα, that which relates horizontally, rather than vertically, like Jesus’s second command to love one’s neighbor as himself. While it was a vital part of the culture to entertain a ξενἰος in the event he was a god, there was also a serious human aspect to the hospitality code as well. Perhaps the best examples of how this code was supposed to work can be seen in The Odyssey. Three times throughout his wanderings, when Odysseus came to an unknown place, the narrator records Odysseus using this expression,

[200] “Ah me, what are the people whose land I have come to this time,

[201] and are they savage and violent, and without justice,

[202] or hospitable to strangers and with minds that are godly?

Interestingly, the three times are as follows: first when he landed on the island of the Cyclops, then when he was shipwrecked on the land of the Phaiakians, and finally when he was carried asleep to his home Island of Ithaka. The importance of this repeated expression cannot be overstated, because each time he says this, it signals an episode that reveals something about the inhabitants’ understanding of ξενἰα.

Before examining these episodes, it is necessary to make two observations. First, note the way Homer sets the polysyndeton “savage and violent, and without justice” over against the later expressions summarized as “hospitality” and “godliness.” To the ancient Greeks, godliness and hospitality were inseparable. Homer is saying, in essence, there is only one of two ways to view a stranger, as godly or unjust, as hospitable or savage and violent. Second, note that even though Odysseus’s visit to the Island of the Cyclops comes after his shipwreck on the Island of the Phaiakians in the narration, it actually comes first in the chronology of his wanderings, which will be important for our purposes.

In book nine (216-565), When Odysseus and his men come into the cave of the Cyclops while he is out in the field, he says the men wanted to pillage the cave and leave, noting theirs would have been a better idea than his, but he wanted to “see if he [the Cyclops] would give [him] presents.”

Odysseus wants to know if the Cyclops is “hospitable to strangers and with a mind that is godly.” When the Cyclops, called Polyphemus, returns to his cave, he addresses them by saying, “Strangers, Who are you?” Their hope for hospitality is immediately dashed—as are some of their heads—because Polyphemus has asked who they are, indicating he is savage and violent and without justice.

He also tells them he neither concerns himself with ξενἰα, nor with Zeus. We are told their hearts were broken and they immediately began to supplicate Polyphemus for hospitality, but it does them no good. After mocking the suppliants for appealing to Zeus, the Cyclops

[288] …sprang up and reached for my companions,

[289] caught up two together and slapped them, like killing puppies,

[290] against the ground, and the brains ran all over the floor, soaking

[291] the ground. Then he cut them up limb by limb and got supper ready,

[292] and like a lion reared in the hills, without leaving anything,

[293] ate them, entrails, flesh and the marrowy bones alike.

Having been plundered by their godless host, Odysseus and his remaining men wait till Polyphemus is asleep, put out his single eye with a glowing-hot, sharpened pole, and escape the cave on the bellies of the sheep. In his escape to the sea, Odysseus rebuffs Polyphemus, shouting,

[475] ‘Cyclops, in the end it was no weak man’s companions

[476] you were to eat by violence and force in your hollow

[477] cave, and your evil deeds were to catch up with you, and be

[478] too strong for you, hard one, who dared to eat your own guests

[479] in your own house, so Zeus and the rest of the gods have punished you.’

Homer is showing the reader monsters are not hospitable; they are “savage and violent, and without justice.” Monsters will get what is coming to them, judgment. To highlight the significance of what is going on here, one might turn the statement around and say, those who are not hospitable are monsters. Whatever else Homer is doing with this episode, he is using the Cyclops, the monster, Polyphemus, to provide a foil for Odysseus’s next encounter with strangers when he is stranded on Sheria, the home of Phaiakians, which takes place in book six.

Note Odysseus has other encounters between his encounter with the Cyclops and the Phaiakians, but the Homeric signal for the reader to pay attention seems to be when Odysseus asks, “what are the people whose land I have come to this time…”

In the land of the Phaiakians (book 6-13), Odysseus is treated with perfect hospitality. They give him a bath, clothing, a feast, a bed, and gifts so numerous, they exceed anything he could have gained spoiling the Trojans. Their perfect hospitality is by similitude of degree inverse that of the monster, Polyphemus. This sets the reader up to consider the final time Odysseus asks, “what are the people whose land I have come to this time…”

The final time he asks the question is when, unbeknownst to him, he is on Ithaka, his own land. At this point the reader is well aware that the suitors of Penelope are wildly violating ξενἰα. Without their rightful king, Ithaka has become an Island of one-eyed monsters—blindly obsessed with feeding their lusts and ravaging Odysseus’ palace. Because they are more like Polyphemus than the Phaiakians in their own land, the reader is prepared to anticipate their demise, a just judgment for the “savage and violent, and without justice.”

With this understanding of ξενἰα, in the back of our minds, a careful reader of the Homeric epics can now return to the question about Helen. It seems it might not be so unreasonable after all, given the mores of the ancient Greeks, to think Paris’s abduction of Helen while a guest in Menelaos’s house—a violation of the strict code of ξενἰα—might after all be the reason for the Trojan War.

How else does a king exact judgment on a one-eyed monster who has plundered his sacred bedroom?

In Book three of The Iliad, there is a gripping episode where Menelaos and Paris are facing off in a duel for Helen, much like David and Goliath in the Hebrew canon. Here Homer gives the reader another glimpse into the serious nature of this ancient ethic:

[349] … And after him Atreus’ son, Menelaos

[350] was ready to let go the bronze spear, with a prayer to Zeus father:

[351] “Zeus, lord, grant me to punish the man who first did me injury,

[352] brilliant Alexandros, and beat him down under my hands’ strength

[353] that any one of the men to come may shudder to think of

[354] doing evil to a kindly host, who has given him friendship.

In the episode under consideration, Menelaos calls on Zeus father to grant him the ability to punish Paris for his violation of ξενἰα. Regardless of whatever other motives Menelaos may have had for coming to Ilion, he claims in this passage that he wants to set a precedent for the next generation so they may shudder to think of doing evil to a kindly host, who has given him friendship.

If Homer is here using Menelaos’s speech as representative of the Achaian society as a whole—and it is hoped that this has been properly established—then the reader is prompted to see a bigger motive for the war than simply getting Helen back for Menelaos. More importantly, they are exacting judgment for a capital crime as a means of preserving the social convention that is so fundamental to their society—to honor the gods, and honor one another by vulnerably showing non-preferential treatment to strangers. The implications here are huge.

First, such a wholehearted commitment to a perfect stranger in the old world when there was not yet a proclamation of the good news would require an equitably weighted response to a violation of such vulnerability and generosity.

Second, in terms of understanding punitive retribution over against rehabilitative corrections, one is forced to wonder if the ancients, though they seem barbaric by our modern sentiments, were not more developed in their understanding of justice, more so than their modern educated posterity. Death would be a significant deterrent to future generations taking advantage of the code of hospitality. And the sacking of the city that harbored the violating fugitive would be a further motivation to participate equitably in matters of civil justice.

To further illustrate the significance of this principle, consider the episode in book six where Menelaos is about to spare Adrestos and deliver him to a henchman to take him back to the ship, and Agamemnon rebukes him:

[55] “Dear brother, o Menelaos, are you concerned so tenderly

[56] with these people? Did you in your house get the best of treatment

[57] from the Trojans? No, let not one of them go free of sudden

[58] death and our hands; not the young man child that the mother carries

[59] still in her body, not even he, but let all of Ilion’s

[60] people perish, utterly blotted out and unmourned for.”

[61] The hero spoke like this, and bent the heart of his brother

[62] since he urged justice.

The narrator says Agamemnon’s call for the utter and merciless destruction of the Trojans is the just recompense for the Trojans’ violation of ξενἰα. To the modern reader, such an extreme repercussion as war may seem inconceivable for such a violation—and perhaps it really is—but in an ancient culture, a violation of this extremely important system of hospitality was a violation against humanity in the largest sense.

In conclusion, if we attempt to look at the Trojan War, the judgment of Paris and his accomplices, through the eyes of the Homeric people, there is little else that can be more devastating to civilization than a breach of this moral code of hospitality—to honor the gods, and honor humanity by vulnerably showing non-preferential treatment to strangers.

To ensure the just and peaceful propagation of civilization with such a gracious and vulnerable approach to community as Xenia, and without the hope of the Christian good news at this point in history, a justice system similar to the Lex Talion (eye-for-an-eye) seems most effective to accomplish this task. Whether or not it is just is another matter altogether.

But how does this answer the primary question this article raises? What is it about the Homeric epics that have resonated so deeply with readers for the past three millennia? The simple answer is the Homeric epics resonate with our deepest human conflict: our passion for justice and our need for mercy. In the final book of The Iliad, the bard pulls back the curtain to show us one of the most poignant scenes in the epic:

[23] The blessed gods as they looked upon him (Hektor) were filled with compassion

[24] and kept urging clear-sighted Argeïphontes (Hermes) to steal the body.

[25] There this was pleasing to all the others, but never to Hera

[26] nor Poseidon, nor the girl of the grey eyes (the goddess Athene), who kept still

[27] their hatred for sacred Ilion as in the beginning,

[28] and for Priam and his people, because of the delusion of Paris

[29] who insulted the goddesses when they came to him in his courtyard

[30] and favoured her who supplied the lust that led to disaster.

All the conflicts of the human experience are exhibited in this final scene with the gods: compassion for the fallen hero, a desire to make a difference when your hands are tied, the satisfaction of victory, the conflict of interest, the bitterness of scorn, the hatred of betrayal, the delusion of lust, the satisfaction of judgment, and the rivalry of powers.

And yet, we see in the most flawed characters, be they heroes, cowards, or capricious gods, a reflection of our own flawed nature that still wants justice for our enemies and mercy for ourselves. Most of all, we see a human code of ethics we all deeply long to possess, whether we call it ξενια, or whether we call it the Great Commandments.