Refusing Heaven

A mostly weak and rambling reflection on my first encounter with the "seriously romantic" poet, Jack Gilbert

Jack Gilbert never crossed my literary radar until a few months ago when I heard someone read his poem, “A Brief for a Defense.” Its vivid realism is jarring, but even more so when you’re confronted with stark ambiguity in what you anticipate will be the narrator’s moral paradigm. Cogitate momentarily on these opening lines:

Sorrow everywhere. Slaughter everywhere. If babies

are not starving someplace, they are starving

somewhere else. With flies in their nostrils.

But we enjoy our lives because that’s what God wants.

Gilbert contrasts a tragically pathetic image of suffering babies, not unlike those in Ivan’s poem in The Brother’s Karamasov, with the rest of us enjoying our lives. Then he concludes with the declaration that God wants it that way.

The ambiguity is compelling. Is he being cynical or recognizing the mysteries of Providence? It’s human to wonder why the condition of evil exists in the world, but it’s the reader’s responsibility to ask whether the narrator is mocking the Christian view or giving a moral lecture.

Reading further, one gets the notion that perhaps the narrator is attempting to justify—maybe to himself—the privilege of enjoying the pleasures of life while others are suffering. Either that or he is attempting to reason through the perplexing mysteries of the human experience. His motive for doing so remains uncertain as he rightly proceeds to explore some of the ordinary delights that make humans human (e.g., admiring the beauty of a wild animal, enjoying a smile or moment of laughter amidst our various disturbing trials). This has the ring of truth and his examples are reminiscent of C. S. Lewis’s in his lecture, “Learning in Wartime,” where he asserts:

We are mistaken when we compare war with “normal life.” Life has never been normal. Even those periods which we think most tranquil, like the nineteenth century, turn out, on closer inspection, to be full of crises, alarms, difficulties, emergencies. Plausible reasons have never been lacking for putting off all merely cultural activities until some imminent danger has been averted or some crying injustice put right. But humanity long ago chose to neglect those plausible reasons. They wanted knowledge and beauty now, and would not wait for the suitable moment that never comes. Periclean Athens leaves us not only the Parthenon but, significantly, the Funeral Oration. The insects have chosen a different line: they have sought first the material welfare and security of the hive, and presumably they have their reward. Men are different. They propound mathematical theorems in beleaguered cities, conduct metaphysical arguments in condemned cells, make jokes on scaffolds, discuss the last new poem while advancing to the walls of Quebec, and comb their hair at Thermopylae. This is not panache; it is our nature.1

Lewis argues that to deny the pleasures of life or one’s opportunities to flourish just because there is grave danger in the world or because others may be suffering when you’re at peace is to miss the point that this is the normal human condition. All of us live every day on the brink of eternity. Essentially, all of life is like fiddling while Rome burns. And, says Lewis, “to a Christian the true tragedy of Nero must be not that he fiddled while the city was on fire but that he fiddled on the brink of hell.”2 In other words, the paradox is more intense than we imagine.

Gilbert, on the other hand, suggests that if we refuse to enjoy the pleasures of life while we can, we only diminish the importance of others’ suffering. Consider the following lines:

If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction,

we lessen the importance of their deprivation.

We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world. To make injustice the only

measure of our attention is to praise the Devil.

Is this true? Is there value in human suffering? Can we diminish it if we fail to embrace our happiness and satisfactions. If, by making injustice the only measure of our attention, we are praising the Devil, what exactly is the proper scope and measure of human attention? Where should human beings set their affections? Lewis would say it makes us monomaniacs to narrow our attention solely on injustice in the world.

Gilbert seems to agree but goes a step further. He suggests we also need to enjoy the incidental pleasures found in our own suffering as well. He says, “If the locomotive of the Lord runs us down, we should give thanks that the end had magnitude.” And, then he asks us to consider whether or not hearing “the faint sound of oars in the silence as a rowboat comes slowly out and then goes back is truly worth all the years of sorrow that are to come.”

Gilbert’s (or his narrator’s) observations are extremely keen, but his suppositions are remarkably ambiguous. This leads us to ask what he means by all of this. Three perspectives seem possible in my estimation: cynical (i.e., that’s what the religious opine), forensic or judicial (i.e., this tension is simply the human condition and we must embrace it), Providential (i.e., a moral God is stewarding the universe toward good ends and even though we are finite in our understanding, we can trust the outcome will be good so we should rejoice when appropriate and weep when appropriate).

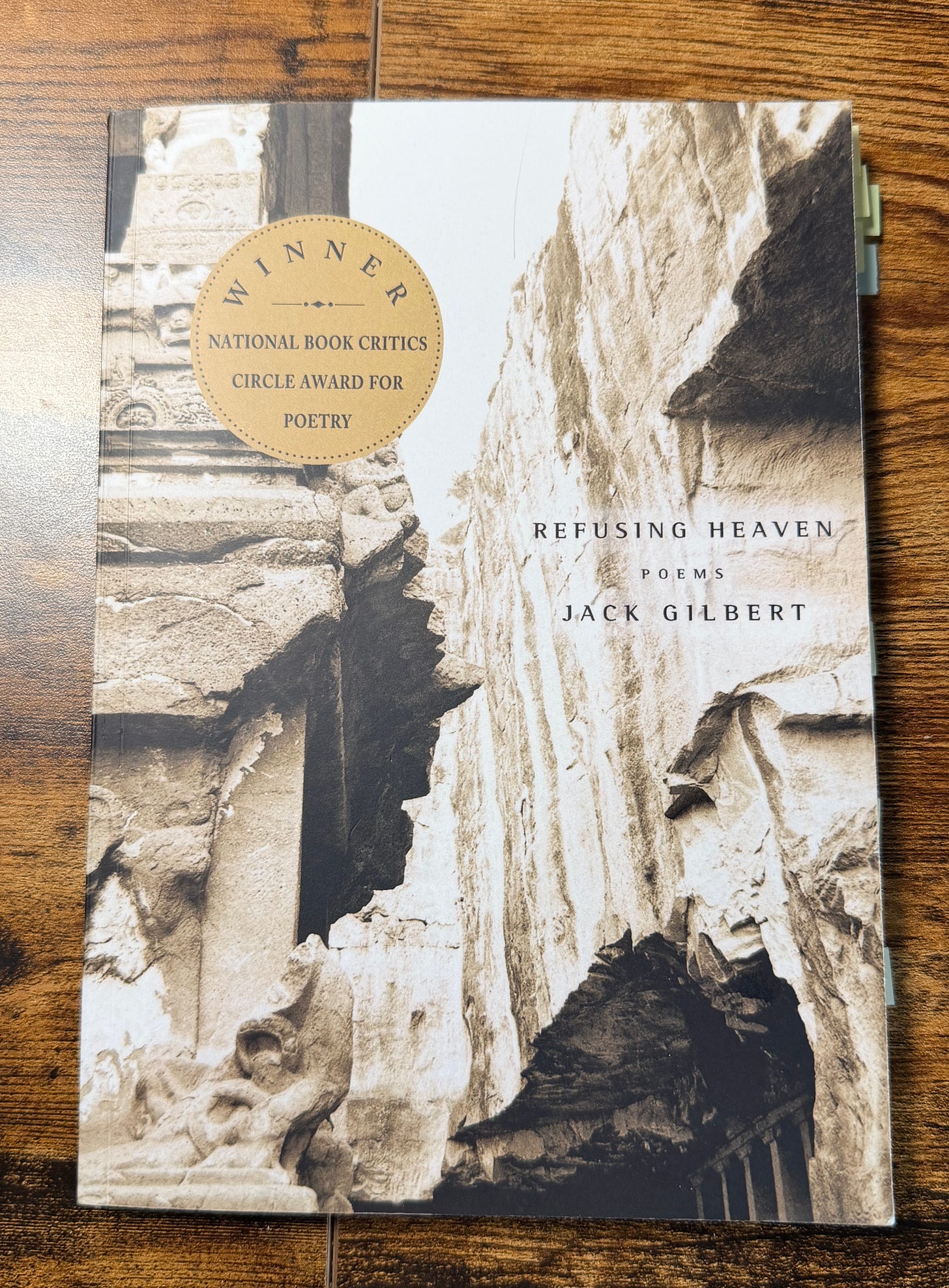

“A Brief for a Defense” debuts as the opening poem in Gilbert’s suitably titled, Refusing Heaven, which won The National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry. The poem from which the title is taken appears on page 60 where the poet’s candor is far less ambiguous:

The old women in black at early Mass in winter

are a problem for him. He could tell by their eyes

they have seen Christ. They make the kernel

of his being and the clarity around it

seem meager, as though he needs girders

to hold up his unusable soul. But he chooses

against the Lord. He will not abandon his life.

Of course, we’re immediately struck by those lines in light of Matthew 16:25: “For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.”

I’m still uncertain what to make of his poetry. What I can say is his style rises above mere meter and verse while never collapsing into prose. Many of the insights are striking simply because they are universally recognizable in a very ordinary sort of way. A few excerpts will hopefully illustrate my point”

From “Adults” (p. 35)

He moves toward her knowing he is about to

spoil the way they didn’t know each other.

From “Less Being More” (p.39)

…He began hunting

for the second rate. The insignificant

ruins, the negligible museums, the back-

country villages with only one pizzaria

and two small bars. The unimproved.

From “Homesteading” (p. 43)

Passion leaves us single and safe.

The other fervor leaves us

at risk, in love, and alone.

Married sometimes forever.

From “A Kind of Courage” (p. 47)

The girl shepherd on the farm beyond has been

taken from school now she is twelve, and her life is over.

I read the entire collections slowly over the course of a couple of months before I ever investigated the author. Jack Gilbert died in 2012 at 87 in Berkeley California. He was acquainted with some “prominent figureheads of the Beat Movement,” but “was unique in that he was not a part of any [literary] school or group. He went his own way, and he lived pretty much entirely for his life and his art.” He published 5 volumes over the course of his career. Other than what you might find on Wikipedia and the fact that he described himself as a “serious romantic,” I know little else about Gilbert.

C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory: And Other Addresses (New York: HarperOne, 2001), 49–50.

Lewis, The Weight of Glory, 48.