On Thinking Christianly

Transcending the Fishbowl That is Secularism

One of the goals of Classical Christian Education is to teach students how to think Christianly. Naturally, it follows that the first question we need to answer is what it means to think Christianly.

At first glance, it seems this expression must mean we are to teach students to think biblically. And that is true, but only part of the answer. It’s not the full story.

In his 1963 book, The Christian Mind, Harry Blamires helps us get closer when he explains,

There is no longer a Christian mind. There is still, of course, a Christian ethic, a Christian practice, and a Christian spirituality. As a moral being, the modern Christian subscribes to a code other than that of the non-Christian. As a member of the Church, he undertakes obligations and observations ignored by the non-Christian. As a spiritual being, in prayer and meditation, he strives to cultivate a dimension of life unexplored by the non-Christian. But as a thinking being, the modern Christian has succumbed to secularization (3).

What Blamires rightly asserts here forces us to drill deeper into the issue of education than the sincerest motivation most Christian parents have for homeschooling or sending their children to Christian schools. Of course, sincere Christian parents want to raise children who subscribe to a biblical morality, undertake biblical responsibilities, and pray and meditate on the Scriptures. This is all necessary and proper. But it is not enough.

Christian children (as well as their Christian parents and teachers) need to be able to think Christianly too. But how is this different than what was noted above? How is this different from Christian piety?

The answer lies in the categories of thought that we take for granted. It is rooted in the presuppositions and frames of reference we never think to question. It’s akin to the old saying, “We don’t know what we don’t know until we know there is something we don’t know.

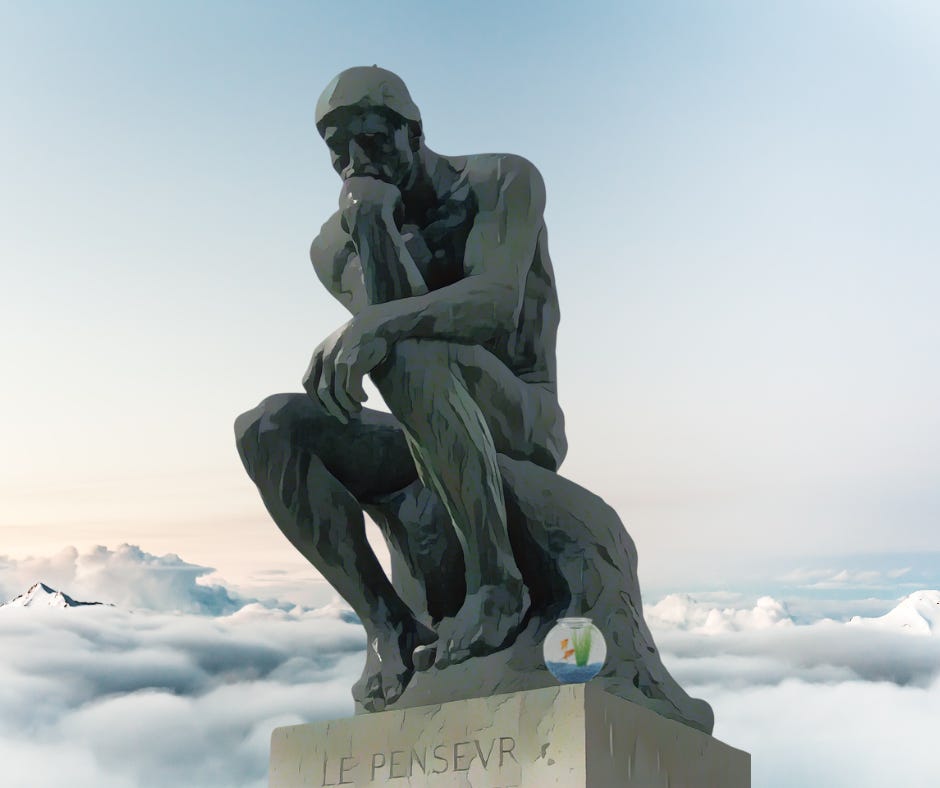

One way to illustrate what I mean is to recount a humorous anecdote the late David Foster Wallace shared in a speech title, This Is Water. He says,

There are two young fish swimming along who happen to meet an older fish. The older fish nods at them and says:

‘Morning boys, how’s the water?’

The two young fish swim on for a bit and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and asks:

‘What the hell is water?’

Irrespective of Wallace’s personal philosophy, his fish story is meant to illustrate the fact that some of the most important realities—ones we would think should be the most obvious to us—are usually the hardest to see. Those of us living in the modern era were born and raised to think in categories and along lines that appear to be our natural habitat. And until we can find some way of flopping ourselves outside the proverbial fishbowl, we will never discover that we’ve been breathing water this whole time.

To put it plainly, I’m talking about Secularism. Secularism is different than secularity, that liminal space the City of God and the City of Man share. Secularism is the view that everything from public education to matters of civic policy should be engaged and conducted without the introduction of a religious or metaphysical element. It is the materialist belief that these matters are in and of themselves neutral and “objective science” is the measure of all things.

Secularism is the water we in the modern world were born into; and we are so used to swimming in it and breathing it, it’s difficult to imagine another reality. It’s also the same fishbowl to which the church and the academy unfortunately immigrated a century or more ago; and now we all (Christians and Secularists alike) have been settled here for so long, we all think in secular terms and the church has forgotten its native tongue.

Blamires explains it this way:

“Except over a very narrow field of thinking, chiefly touching questions of strictly personal conduct, we Christians in the modern world accept, for the purpose of mental activity, a frame of reference contracted by the secular mind and a set of criteria reflecting secular evaluations” (4).

Said another way, although most Christians seek to live a life pleasing to God, personally, and want to raise their children to do the same, they think about everything–even their Christianity–in secular terms. Secularism is, in most cases, the framework by which modern Christians organize their categories of thought, it is the standard by which they evaluate the quality and cogency of those thoughts, and it’s the schema by which they imagine their identity and existence.

A case in point is how so many American Christians’ sense of justice is rooted in Naturalism (i.e., “the advantage of the stronger”) and not Christian ethics. Further, most Christians tend to discuss ideas of Justice and Liberty (and others like them) in secular terms without even realizing it. Another glaring example is the modern church. The modern American Evangelical Church is, in large part, deeply rooted in secular categories of thought, like corporate leadership strategies and critical race theory (i.e., social justice).

Summarily, and to the point of this article, secularism is the water in which most Christian parents are seeking to teach their spawn to swim like Christians.

My thesis is this does not work in the long run, and a liberal arts education is an essential part of developing a proper frame of reference that transcends the fishbowl that is Secularism, so Christian parents can teach their children to think Christianly.

I love you harping on Secularity vs. Secularism. Super helpful framework.